Could it happen here?

Could it happen here?

The recent news that the government of Cyprus is considering a one-time tax on the saving deposits held at Cyprus based banks is yet another example of the riskiness of holding more than a nominal amount of cash in a bank account. While Cyprus if far different from the United States, both in terms of the fiscal state and banking oversight, it’s yet another example of why savers and investors need to be vigilant in mitigating the risk to their supposedly risk-free assets.

We spend much time and effort trying to educate investors that leaving cash in a bank account is tantamount to giving the financial institution an unsecured loan. If all goes as expected, the entity will return your money, along with a few basis points of interest, when you want it. If the bank “stumbles” in one way or another, the depositor may or may not get most, some, or very little of their money back, at some point in time.

Financial regulators would have us believe that the risk of a major financial stumble has been reduced to the equivalent of the one in 100 year flood, but the capital markets have been forced to confront the one in 100 year flood annually. Despite the heightened frequency, investors remain complacent to such a risk. Over the course of the last five years, unlucky savers have had their cash encumbered by the fall of Lehman Brothers, the failure of The Reserve Fund, the failure of MF Global, the collapse of UK-based Northern Rock plc, the collapse of the Icelandic banking system and now the potential for outright theft of cash from Cyprus savings accounts. The list of banks that have been forced into a near-panic situation due to their own malfeasance is nearly as long, and includes HSBC and Standard Charter Bank, accused as money launders to the terrorist and drug dealer community, UBS, with their alleged proactive strategy to help U.S. citizens evade U.S. taxation, and the multitude of money center banks that are facing enormous legal liability for manipulation of the LIBOR interest rate. We also believe that money market mutual funds are equally fraught with risk. Investors seemed to have forgotten the dire and urgent warning sounded by former Securities and Exchange Chairwoman, Mary Schapiro, that the money market industry poses substantial systemic risk to investors and the capital markets. Ms. Schapiro, together with former Treasury Secretary Geithner, drafted a proposal to the Financial Stability Oversight Council requesting immediate action. Unfortunately, with the change in the administration, it appears those concerns have fallen by the wayside.

Given that list of “eyebrow raising” failure and malfeasance, one would expect that investors would demand substantial compensation to make an unsecured loan to these financial entities. Instead, according to the FDIC, the average savings deposit rate in the United States is 0.07% per annum. Similarly, the average return on a taxable money market fund in 2012, according to IMoneyNet was 0.04%. Such miniscule returns hardly seemed commensurate with the risk assumed.

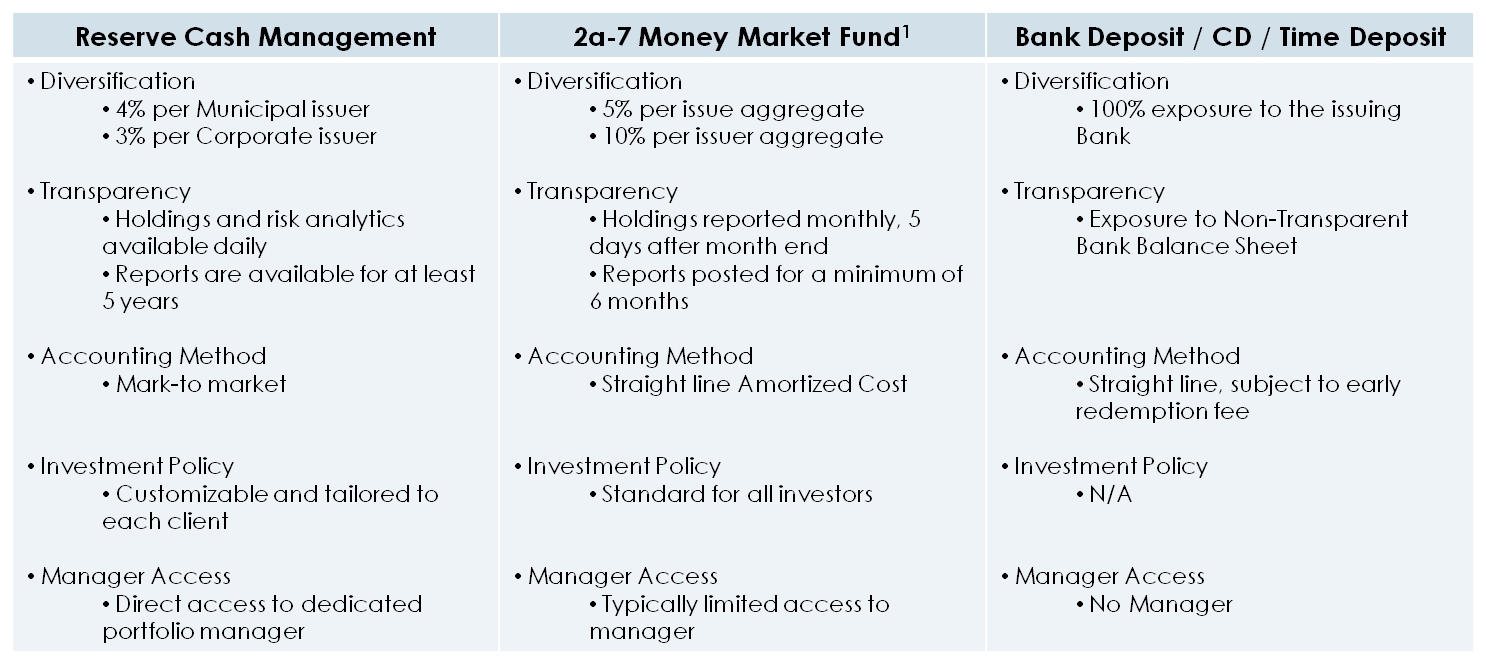

At Halyard we believe that investors deserve a more sensible alternative to money market funds and bank deposits. That is why we established the Reserve Cash Management Portfolio Strategy (RCM). The RCM is designed to provide an alternative to money market funds and bank deposits with the primary objectives of preserving principal and providing liquidity. However, unlike money market funds each account is separately managed and customized to deliver attractive yield while meeting the specific goals and objectives of the client. That structure mitigates the risk of an unforeseen 100 year flood wiping out what had been considered cash. The graphic listed below offers a side-by-side comparison of the RCM versus bank deposits and money market funds.

Please call or send an e-mail if you have any questions.

1 Source: Rule 17 CFR 270.2a-7 of the Investment Company Act of 1940.